City Press article

-CITY PRESS

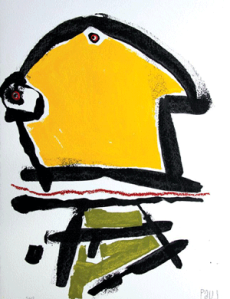

Pretty little monsters

2012-09-16

by Percy Mabandu

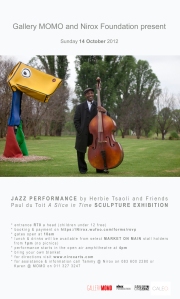

Painter-sculptor Paul du Toit is exhibiting in his native city of Joburg for the first time. Percy Mabandu looks at his use of an almost infantile-like style to create high art

Having successfully carved himself a comfortable career internationally, Cape Town-based artist Paul du Toit hangs his first major solo exhibition in Joburg at Gallery MOMO.

The show runs concurrently with another one at the Nirox Foundation near Maropeng, the Cradle of Humankind.

The MOMO show includes paintings and only two sculptures, one bronze plus a mix-media figurine. The Nirox show includes sculptures.

This provides a visual resonance between the two connected shows. The body of work is made up of 24 paintings and four drawings. A few of the works are from as far back as 2006, but had never been shown in public before.

It’s an impressive collection, given the large size of the work. “I do about 46 to 48 works per year,” says Du Toit, hunching over the bronze sculpture, titled First Glance. He then offers that this sculpture is his first love. “But I’ve kept it a secret for a long time.” This fascination with carving and shaping is evident in his treatment of the base surface of his painted works.

Du Toit mixes marble dust with white paint, creating a thick paste to prime his canvases. He applies this plastic substance generously to manifest instant forms. He then uses cardboard sheets, knives and other carving tools to produce patterns. Once the surface is dry, he responds to apparent textures with his bright-coloured paints, almost like relief drawings. He imposes independent images on to others.

Paintings like Long Match, Gigantic and Call This Dancing are exemplary of this technique. The tall man with a bald head and an easy laugh says he uses long brushes, like Chinese calligraphers do, to paint. He also uses rollers with long handle sticks. The technique minimises his force and gives his wrists an easy grace to make lines.

“I force myself to be uncontrolled so I can keep things pure. I want to create something no one has seen before and I haven’t seen. One must struggle to be as original as possible.”

Born in Mayfair in 1965, Du Toit moved to Cape Town 17 years ago when his daughter was born. He owns a studio in Brooklyn, New York, and has worked in Beijing, and hosted exhibitions in Paris and Amsterdam. As a child, he suffered from rheumatoid arthritis. It was at this time he started to produce art consistently. He spent a long time in a wheelchair while undergoing treatment at the then Joburg General Hospital.

His aunt Elizabeth van der Sandt, also an artist, took an interest in the art therapy lessons Du Toit was receiving at the hospital. She brought him art books of European artists like Joan Miró and others whose work is echoed in his art today. In 2009, Du Toit again had to undergo a medical operation. This time to cut out a nerve infected with melanoma. Following this, he took his family on holiday to New York.

There, he made friends with people like Ouattara Watts, the Ivory Coast artist who made canvases for the late art superstar Jean-Michel Basquiat. The latter is also a great influence on Du Toit. The use of black outlines, bright, broad, flat colours and oil sticks tell of this influence.

Du Toit’s quirky characters, like Basquiat’s, may also be seen as self-portraits of sorts. “All art is self-portraiture, I guess,” Du Toit says, then chuckles with his fingers pointing to his half-swollen neck and face. He says people often say his crude figures look like him because of the scars from his cancer operation.

At 47, Du Toit has a child-like appeal about him. His use of an infantile-like style to address high art objectives has admirable precedents in South African modern art history. Light-hearted visual language links up with efforts by deceased South African greats like Walter Battis, for instance. Their use of colour and their approach to abstraction is a case in point. The iconic compositions and calligraphic style suggest more can still be done with the surface of the painted work.

Asked how he knows a painting is finished, the American painter Jackson Pollock answered with another question: “How do you know when you’re finished making love?”

Du Toit has his own ideas: “I always say it has to be ugly enough. Then I know it’s complete.”

– CITY PRESS